Stockhausen 1970 - New music downunder

Karlheinz Stockhausen in Australia 1970

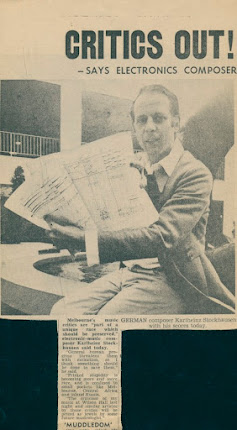

Melbourne’s music critics are “part of a unique race which should be preserved,” electronic-music composer Karlheinz Stockhausen said today. “General human progress threatens them with extinction, so I think something should be done to save them,” he said. “Printed stupidity is becoming more and more rare, and is confined to small pockets like Melbourne, Central Africa and inland Russia. The criticism of my music

at Wilson Hall last night and similar articles by those critics will be prized as jewels by some future musicologist.” April 1970.[1]

|

| Critics Out! – says electronics composer. |

Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007), author of the above acerbic comments, was a controversial, yet innovative, German composer who briefly toured Australia during April 1970 in between participating in the international Expo 70 fair which was held that year in Osaka, Japan. Stockhausen took a break from his performance and presentation duties to fit in a 10-day tour of mostly university campuses. The visit was reported at length within the local newspapers, and both the composer and his performances drew crowds and controversy. Stockhausen was up front in regards to the innovative and often provocative nature of his work and innovative electronic musical production. Audiences were often split between those who were attending in order to experience something new, and those who were true fans. The following extracts from local media and other reports of the tour, along with commentary by the author of this blog, will hopefully assist in bringing to wider attention the important role Stockhausen’s tour played in supporting and enhancing the experimental music and intermedia performance art scene in Australia during the early 1970s.

Stockhausen's Australian itinerary 1970

Details of the tour are sketchy, with precise dates of various performances unknown at this stage.

April

- Friday, 10th - Arrival in Sydney from Japan.

- Saturday, 11th - Sydney Conservatorium of Music.

- Sunday, 12th - Science Theatre, University of New South Wales.

- Monday, 13th - Hobart.

- Tuesday 14th - Albert Hall, Launceston.

- Wednesday, 15th - Science Theatre, University of New South Wales.

- Melbourne. Wilson Hall, University of Melbourne. Three performances over three days.

- Elder Hall, University of Adelaide.

- Perth.

- 20th April - Stockhausen leaves Australia and returns to Expo 70, Osaka, Japan.

-------------------

Expo ‘70

Karlheinz Stockhausen arrived at Sydney airport on 10 April 1970, having flown from Osaka where he was performing in the dark blue, spherical concert hall specially built by the West German government for the Expo 70. Whilst in Australia he noted that his music had already been presented before some 2 million people attending the exposition, such was the success of the event and the interest his performances drew from both local and international visitors.

|

| German musical pavilion at Expo 70, Japan. |

The pavilion's design was based, in part, on Stockhausen’s concept for a performance space, with an obvious nod to the influence of American architect Buckminster Fuller and the geodesic dome which he had developed after the end of World War II.[2] Within the concert sphere space, Stockhausen’s composition Expo was performed throughout 1970.[3] It was a composition for three performer with short-wave radio receivers and a sound projectionist. Expo was typical of the music coming out of Stockhausen's Cologne studio during the latter part of the 1960s. The composer and performer's decision to visit Australia may have been based on recent encounters with Australian musicians and composers such as David Ahern who had travelled to Germany specifically to work with him there.[4] As a result, he may also have been aware of the fact that there was a developing experimental electronic music scene in Australia which would welcome his innovative sound design. Therefore, a brief visit Downunder was deemed worthwhile.

Australia ‘70

Stockhausen’s Australian tour was organised by Fine Music Australia Pty. Ltd. and comprised a series of lecture–demonstrations and performances at various music venues and university campuses. These events were often based around non-traditional, amplified electronic instruments such as synthesizers, tape machines and electronic devices including the Theremin. The Theremin was made most famous with the younger generation due to its use by guitarist Jimmy Page in the middle section of Led Zeppelin's landmark Whole Lotta Love, released in November 1969. Stockhausen's personal interaction with audiences was also a unique, and often controversial, part of his performance. On 11 March the Sydney Morning Herald published a report in anticipation of the visit:

Arts and Entertainment - Brief visit to rock world

No powers of prophecy are needed to forecast that Karlheinz Stockhausen's brief visit next month will start reverberations that will continue long after the visit. Stockhausen has maintained his position as an international leader in the use of advanced and radical musical techniques and as a rallying point for the musical avant garde for 20 years. He will give three lecture-demonstrations in Sydney, using special equipment for reproducing taped recordings. The first will be at the Conservatorium on April 11, the others at the Science Theatre, University of N.S.W., on April 12 and 15 immediately after the English Opera Group season. Similar lecture - demonstrations in Europe and America are regarded as major musical events. His London lecture in January generated more discussion than an entire concert season.

Born in 1928, he studied with Frank Martin, Milhaud and Messiaen and became known to the musical world through his early electronic music compositions produced in a new studio in Cologne. At the same time he was composing pieces of original design and construction for conventional instruments, and has followed them with major works for multiple orchestras and choirs and, more recently, with music which relies to an increasing extent on the responses of the individual performers.[5]

Members of the local avant garde music scene were therefore looking forward to the visit and sought to engage with the German through active support and attendance at his concerts. A pointer to this was the series of prior concerts held in Sydney during February 1970 which featured a number of Stockhausen compositions. These included ‘Prom' concerts at the Sydney Town Hall, among which was a performance of Stockhausen’s ‘Song of the Youths’. A lively review of the event – featuring the work of local composers Peter Sculthorpe and Tony Morphett and termed ‘Love 200’, marking the 200th anniversary of the European 'discovery' of Australia by It. James Cook commanding HMB Endeavour – was presented by F.R. Banks in his critical review within the Sydney Morning Herald. It was noted therein that the performance was extremely loud, apart from being multi-faceted:

Earth Shattering End

With "Love 200", the lavishly publicised musical hybrid which brought the Proms to an ear-shattering end at the Town Hall on Saturday evening, composer Peter Sculthorpe gives public notice that he has sold his soul cheerfully to the Devil. The contract, one hopes, is temporary and revocable, for Sculthorpe's new "Hair"-style can, at the very best, be regarded as a successful failure. The success is one-sided, the failure many-sided. "Love 200", unlike Captain Cook who gets the blame for inspiring it, charts no new territories but merely alternates pop songs (lyrics by Tony Morphett) and instrumental interludes in an atmosphere of rock-bottom sensuality in which the Sydney Orchestra under John Hopkins, Tully (the pop quartet which played for "Hair ') and singer Jeannie Lewis are aided and abetted by a delirium of light effects, a battery of oversexed microphones, and a gentle puff of diabolic fog - a fiasco, this - by Ellis D. Fogg. The one side of success was inevitable - its sources, the novelty shock value, the sheer decibel bull market, the hint of a practical joke in finding this Trojan horse in a A.B.C. stable: all this had a built-in entertainment guarantee for the good-natured audience. It was as funny as being served a meat pie at a gourmets' dinner.

The causes of failure were these: Too loud a volume to allow an appreciation of what was really going on orchestrally behind the facade of pampered eccentricity or to permit an understanding of the words; too much unrelieved frenzy and, above all, a repression of idiom into well-worn pop grooves. I am absolutely certain that behind all this were ideas with all of Peter Sculthorpe's customary ingenuity and value (the stereo effect of musicians in the upstairs galleries, for instance) but they foundered in an ocean of noise. "Love 200" is the progeny of a shotgun wedding between serious contemporary music and pop on the very lowest common denominator. It falls short of success and - finally - must not be taken too seriously.

More impressive in its way was the non-work which began the concert. The fractured electronic noises of "Gesang Der Juenglinge" ("Song of The Youths") by leading German avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen were amplified from a 4-track Cologne Radio tape while multi-coloured lights, wired to volume, flashed and played ghostly chasings around the blacked out Town Hall.

I found this a fascinating experience; the religious text, boy soprano voice and chorale-like sound collages all fused into a unified work of art independent of, and not to be judged by, strictly musical standards. The rest of the concert paid homage, with a program rather like the witches' brew in "Macbeth," to second-rate music except when, as for Malcolm Williamson's trashy postcard-Spanish overture "Santiago De Espada," it descended to the third-rate. Schubert's fluffy Symphony No. 3 was lightweight pleasantry even though slowish tempo kept the allegro of the first movement and the minuet earthbound, while Percy Grainger's "Danish Suite" — homely grandmother music rummaging in folky drawers - was given all that buoyancy which John Hopkins so tirelessly commands. Two other musicians shared the spotlight - pianist Gustave Fenyo as a soloist of strong, quickfire dexterity in Saint-Saens' Piano Concerto No. 4 and cellist Lois Simpson, the target of an affectionate farewell by her colleagues on the occasion of her swansong with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Also during February 1970, David Ahern had staged a 24 hour concert at the Watters Gallery, Sydney, with the performance heavily influenced by his recent work with Stockhausen in Cologne.[7] The Sydney Morning Herald followed on its 11 March notice of the German’s impending visit a story on Friday, 5 April, being a fulsome report from Lynne Bell in London. It included an image of the young composer.

Composition for Oboe and Transistor Radio

“He makes music with crackles, squeals, bangs and shouts . . ."

From Lynne Bell in London

One of Europe's controversial "electronic" composers will be in Sydney next weekend for a series of lectures. Here is a look at his stormy approach to music...

Karlheinz Stockhausen, the 41-year-oId- German composer, soon to visit Sydney, likes to think of himself as an engineer. When he composes he sees music as a mathematical graph. When he is conducting that music he substitutes complex electronic equipment for the traditional baton. Stockhausen, a product of the post-war European musical revolution, is one of the few "sonic" music composers regarded as great in his own time. Fourteen years ago, he became the first to compose a score - or diagram - for electronic music. In this, the notes are depicted as mathematical graphs showing how anyone with a tape recorder and the necessary electronic equipment can reproduce the sounds. Since then, Stockhausen has travelled the world, spreading his idea of freer musical interpretation through the interplay of traditional instruments with electronic equipment. His personal appearances are always marked either by enthusiastic appreciation or howling disbelief. Last summer, an Amsterdam performance of his works ended in uproar when, after 20 minutes of listening to six singers rhapsodising in German on one note, the audience demanded to know: "When will the music start?" The concert audience jeered and clapped and refused to allow the singers to continue until Stockhausen answered their question. He didn't. And they went home. A month later, at the British premiere of one of his works at Cheltenham, half the audience jeered and the other half applauded his performance of "Spiral," a work for oboe and transistor radio. "The Times" music critic described the work as full of "atmospherics, crackles, squeaks, bangs and amplified shouts."

Most of Stockhausen's music has two levels - a stream of conscious music treated electronically, either amplified or fed back through a distorting machine, and beneath it a line of noise which can be anything from human sounds of hiccups, speech and laughter to deep breathing or hand-clapping. As a musical explorer into a new world of sound, Stockhausen accepts the criticism and adulation as reflections of an uncertain musical understanding. Some people find his music funny, others regard it as monstrous, many hate it and quite a few think it is inspired by genius. He doesn't mind what the reaction is - provided it is honest. He told a London audience last year that a boyhood spent under the Third Reich had taught him it is wrong to tell people what they should feel and think.

Stockhausen's extreme modernistic style is based on Webern's 12-note idiom and covers a wide field in that it allows for the use of most known instruments as well as voice. The score is often so loosely written that any two performances can be totally different, depending on the conductor's interpretation of what Stockhausen means. This is why the composer regards all his music as "his" only when he is manipulating the electronics equipment. "Visual music is giving way to aural music, the score to records or tapes," Stockhausen says when tackled on the issue of his departure from the traditional form of musical notation. He has already liberated the creativity of performers by allowing them freedom of interpretation. He next wants to liberate audiences. His ideal concert hall would be a central platform suspended over the various orchestral and electronic placements which would totally "immerse" the listener in Stockhausen sound.

Local music correspondent Roger Covell published an article in the Herald’s Entertainment and Arts section on Friday, 10 April. It comprised an enthusiastic report on the forthcoming tour.

Leader in new music

By Roger Covell

The sequence of events in [the] Science Theatre at the University of New South Wales this week and next week would be hard to match in distinction in Australian musical history. The English Opera Group ends its season of church parables rehearsed under Benjamin Britten's direction, on Saturday night. Then, on Sunday morning, Karlheinz Stockhausen, the most consistent leader of new developments in music in the past 20 years, will move in to test his high-powered amplification equipment for a lecture demonstration on "live" electronic music on Sunday night.

Stockhausen arrives in Sydney this morning from Japan, where he has been giving demonstrations of his recent musical activity at Expo 70 in Osaka. His first Australian lecture-demonstration will be in the Conservatorium tomorrow night. He will talk about new electronic music on tape and his own approach to what he calls a "universal music." He follows this with his Science Theatre lecture demonstration on Sunday evening and then with another Science Theatre session next Wednesday on some basic principles of electronic music. Between his Science Theatre appearances he will fly to Tasmania. After then he will give similar lecture-demonstrations in Melbourne and Adelaide. Because of all this rapid hopping about, Fine Music Australia of Melbourne, which is presenting Stockhausen's Australian tour, has had to charter a plane to carry four 90 watt loudspeakers and other sound producing equipment he will be using at his lectures.

Stockhausen, born in 1928, first came into international prominence with electronic music compositions introduced at the studios of the West German Radio in Cologne. Since then he has experimented with serialised control of all the aspects of musical sound and with many kinds of spatial grouping for performers. Some of his most startling departures in recent years have been in the realms of indeterminate music, in which he seems to have given steadily increasing freedom to performers in the interpretation of his written directions. Whether you like what Stockhausen does or not, his lecture-demonstrations are not to be missed. He is a particularly compelling speaker and demonstrator. I had the good fortune to attend a lecture he gave in London in January at which he held a packed audience spellbound with the details and sounds of some of his most recent works. His lectures in Europe and America have already been recognised as a major factor in the exposition of new directions in music to a wider audience than that which can absorb them without some preliminary explanation.

------------------------------

A notice in the April 1970 issue of the Australian Journal of Music Education provided more specific information on the imminent visit:

Karlheinz Stockhausen Visits Australia

One of Europe's most distinguished present-day composers and one of the pioneers in the field of electronic music, Stockhausen is Director of the famous Studio for Electronic Music at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk. This visit to Australia from April 11 to 21 will follow his participation in the Osaka Expo '70 where performances of his music will form part of the German Federal Republic's contribution. Mr Stockhausen will be using the most advanced electronic equipment for his unique series of concert lectures which will be given in Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart, Launceston, Adelaide and Perth under the general direction of Fine Music Australia Pty. Ltd.[8]

Stockhausen would squeeze in a great deal of activity during his relatively brief two week visit to Australia, covering all the major Australian capital cities except for Brisbane. Upon his arrival in Australia on Friday, 10 April, the Sydney Morning Herald published an interview and brief summary of his career to date.

Stockhausen - Protest drowned his first composition; now he’s Master of ‘machine made music’

"When the vocal protest at the performance of my first composition drowned the music out, I knew I really had something to offer." German musician Karlheinz Stockhausen was talking about the early days in Germany, where he received formal training as a pianist at the State Conservatory in Cologne. He arrived in Sydney yesterday for a 10-day series of lecture recitals in five States. Whatever the initial audience reaction, Stockhausen is now recognised as one of music's leading and most consistent innovators. Born in 1928, he established the first electronic music studio in the world at Cologne when he was 24. His experiments with electronic music forms, combined with a unique attitude to concert performers and audiences, have resulted in more than one incident over recent years.

"In Bonn three months ago I performed all night, using four halls in one building. In 15 hours, two-thirds of my whole life's works were played. The resident 80-piece orchestra was placed around the walls of the entrance, but not being able to perform in this type of concert environment, they walked out half-way through. At the entrance, we hid blackboards listing the choices in the four halls. This, of course, demands people who can make choices — and not just run in like chickens after food. In the end it didn't really matter, because everything we were playing was so new. No-one had heard any of it before."

Stockhausen described large formal orchestras as "the remnants of a society which is dying away," and forecast their demise "within 40-50 years."

"The days where you had 30 to 40 violinists just to make the music sound a little 'fat' are disappearing. But the present system is being maintained artificially by the musicians themselves, who are naturally enough concerned with their own security. I think we will eventually have music performed by small groups of independent specialists, who will travel a lot," he said. "For instance, at Expo 70 in Osaka, I played to two million people. It would take me years to reach such an audience using the present concept of concert style."

The first of Stockhausen's three lecture recitals in N.S.W. will be held tonight at the Conservatorium, where taped selections of his compositions will be played through four 90-watt amplifiers.[9]

Little has been published concerning Stockhausen’s 1970 Australian visit and lecture tour apart from minor comment at locations such as the University of Melbourne Grainger Museum website. The following, for example, is a brief note relating to a collection of newspaper clippings held by the museum and summarising the tour:[10]

Karlheinz Stockhausen in Australia, 1970

German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen visited Australia for ten days in April 1970. He gave concert-lectures on electronic music around the country, including three programs in Wilson Hall, at the University of Melbourne. Delivered through a battery of speakers, Stockhausen’s electronic music ‘transformed Wilson Hall into a vast and sometimes terrifying acoustic cave’, according to a local newspaper. Performances included his Telemusik (1966). The Grainger Centre electronic music enthusiasts, including Keith Humble, Ian Bonighton and Agnes Dodds, helped set up Wilson Hall with the electronic equipment. Stockhausen was apparently very demanding, and Wilson Hall was not the ideal venue, with not enough power points for all the equipment.

|

| Source: Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne. |

Rudolf Pekarek of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra also collected material relating to the visit, and this is now held in the Fryer Library, University of Queensland, though its contents have yet to be analysed in any detail.[11] What is known, however, is that David Ahern was engaged as Stockhausen’s assistant for the tour.[12] He accompanied the German to the various capital cities and assisted with arrangements for equipment and accommodation. Though the precise details are sketchy, Stockhausen is known to have presented his lecture demonstrations in Wilson Hall at the University of Melbourne; at the University of Adelaide and the Elder Hall there; at two venues in Sydney – the Conservatorium of Music and the John Clancy Auditorium (Science Theatre), University of New South Wales; and also in Hobart, Launceston and Perth.[13] His precise activities in the latter three localities are not known at this stage. Following his arrival in Sydney on Friday 10 April, he appeared the following night at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. A brief report on this first Australian performance appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald of 12 April, as follows:

Conductor sits with audience

German musician Karlheinz Stockhausen last night conducted his first Australian performance while sitting in the midst of his audience. But that's usually the way it is for the 41-year-old composer of electronic machine made music. The stage is bare and the lights are dimmed as Mr Stockhausen conducts his tape-recorded concert lectures. Last night's performance at the Sydney Conservatorium was the first of a series of three to be given in New South Wales. At the concerts Mr Stockhausen plays taped music, produced electronically, from four 90-watt amplifiers. He controls both the pitch and tone of the sounds from a seat about 10 rows from the stage. During the recitals he also lectures on the method and form of his compositions and answers questions. He is in Australia on a three-week visit during a break in his concert schedule at the West German exhibition at Expo 70, in Osaka.

A deal of information was contained in the advertisement published in the Herald leading up to the performance. For example, it was noted that Stockhausen would perform his compositions Hymnen and Telemusik at the first concert, Mikrophone and Aufwarts at the second, and discuss four criteria of electronic music at the third.

|

| The revolution in music – Stockhausen [advertisement], Sydney Morning Herald, 10, 11 and 12 April 1970. |

By far the most comprehensive record of Stockhausen’s time in Sydney is Roger Covell’s reviews in the Sydney Morning Herald. A series of three extended reports were published between 14-16 April 1970 and are reproduced below. In the first piece Covell highlights the maturity of Australian audiences and reviews the performance at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music on 10 April.

Stockhausen mixes humour, feeling [14]

By Roger Covell

A leader of the forward wing of music for nearly 20 years and the author of some formidably opaque articles on musical structure, Karlheinz Stockhausen might have been expected to speak in person like a computerised orator. But, as his first Australian lecture-demonstration in the Conservatorium on Saturday night confirmed, this world-renowned German composer talks clearly, vividly and with a mixture of throwaway humour and strong personal feeling. Even the evening's steady stream of latecomers failed to shake his equanimity in any way. Was the much younger Stockhausen of the early 1950s, the uncompromising rule-maker who called for the serialisation of all the variables of music, as tolerant as this? I don't know. But my guess is that Stockhausen has learned a lesson from the American John Cage in how to absorb all the haphazard incidents of public performance into unruffled musical systems of behaviour.

He seemed to authorise this speculation when he pointed out that his choral instrumental "Moments" included, among many other fascinating ingredients, words representing the reactions of audiences to his earlier compositions. Some of these reactions, incidentally, were far from appreciative. It is possible — who knows? — that a future Stockhausen piece will incorporate the entrances of latecomers: orchestrated and subtly rhythmic entrances, perhaps, that will illuminate as never before the whole practice of late-coming. Certainly, Stockhausen appeared to me to bring us an inspired use of concert-hall behaviour in live performances of his "Moments," when the applause for the conductor's entrance prefigures the antiphonal clapping that begins the piece.

I was slightly perturbed to hear Stockhausen say that he had substituted "Moments" for the scheduled "Hymnen" on the grounds, if I understood him correctly, that its use of conventional choral instrumental forces might be less disconcerting at the outset for an audience here. If Stockhausen's advisers had given him the impression that Australian concertgoers are markedly more conservative than audiences elsewhere, I think they have misled him. Audiences here are much on a par with those of Europe in their average reactions to recent music.

My impression is that Stockhausen would have had to work fairly hard to shock or seriously disturb most members of Saturday's audience. Stockhausen was in any case not trying to shock anybody on Saturday. The forming principle of "Moments," according to which the successive moments may have no logical relationship, is undoubtedly different in theory from the cause-and-effect process that we apply to most of our lives and music (whether it remains different in practice is open to doubt, if only because of the continuum provided by the presence of the same performers).

TELEMUSIK - His "Telemusik" could also provoke arguments, not so much because it incorporates "found objects" (or, rather, something like the X-ray patterns of found objects) of music from many cultures, but because of Stockhausen's belief that it represents a step towards a universal music (Universal for whom? Perhaps only for Stockhausen, unless his hearers are equipped with the clues he dropped on this occasion). Or that it represents a practice different in kind from musical college. Yet the predominating impression of his talking was of the health and even nobility of his view of music and the conviction with which he used currently suspect words like spirituality.

The 1970 Stockhausen seems to be engaged in providing music with a new soul, rescuing it from the aridity of an inbred

delight in its technical secrets. A review of Stockhausen's second lecture demonstration in the Science Theatre will appear tomorrow.

----------------------------

Covell’s second and third pieces focus on Stockhausen’s performance at the University of New South Wales.

Poetic consistency and logic in Stockhausen [15]

By Roger Covell

Stockhausen at the University of N.S.W on Sunday night was less philosophically world viewing but considerably more accessible and heartily embattled than at his first lecture demonstration on Saturday. The Science Theatre suited him, and his music beckoned in appearance, sound qualities, closer confrontation of speaker and audience and cooler temperature, even though one of his hearers complained with justice about the sound level of the air conditioning system.

Stockhausen's command of English proved more than equal to turning the clumsy barbs of one or two boorish questions to his own advantage. But most of the questions from a predominantly young audience were intelligent and genuinely inquiring; and Stockhausen generously let them go on informally long after the programmed part of the evening was over. As before, he used humour to dispel the aura of the esoteric while actually, as he admitted, embracing everything that the word esoteric is likely to conjure up.

Anticipating a possible query as to why he had chosen a tam-tam (large gong) as the sound source of his "Mikrophonie I," he disarmingly pointed out that he might just as easily have used an old Volkswagen. Or, yes, even the human body. He, himself, used the word "esoteric" in the verbal instructions that constitute the score of a recent composition entitled "Upwards" ("Aufwaerts"). I am sure the average orchestral musician would take refuge in other, homelier words if asked to play from a set of directions which begin more or less as follows:

"Play a vibration in the rhythm of your smallest particles. Play a vibration in the rhythm of the universe. Play all the rhythms which you can distinguish today between the rhythm of your smallest particles and the rhythm of the universe . . ."

But would the sceptical, scornful response predictable from many practising musicians be justified? The recorded performance — 29 minutes of it, no less — which Stockhausen played as evidence of what could be done in response to these instructions was a work of considerable poetic consistency and often of dream-like logic. What did it represent as a musical achievement? Stockhausen refused to call it improvisation, but what he denied was simply the process of improvisation on given material or within a traditional set of conventions. It was intuitive music making, as he said, but it was also improvisation; and its hidden conventions were the empathy and tact developed by half a dozen superb musicians working with each other for some years.

Extension - It was also, I think, a logical extension of the forming principle of "Mikrophonie I," in which graphic notation governs the interaction of exciters (the musicians who produce sound from the tam tam's surface), microphonists and the filter and volume controllers. As Stockhausen said, he offered a process of composition rather than a piece in the ordinary sense. For both "Upwards" and "Mikrophonie I" he creates the circumstances in which a performance can occur. Or, to paraphrase him again, he composes not the sounds but the way to produce the sounds.

I personally preferred the results in sound of the intuitive "Upwards" to the cosmic thunders and high lying transparent sound strata in "Mikrophonie I." It seems reasonable to wonder whether Stockhausen's works would be better, or at least just as effective, if they were shorter. Perhaps he calculates that a substantial length is a necessary condition for it to be possible for the listener to surrender to the play of the experience in the way that Stockhausen seems to want him to.

If you would like to take part in this inspection of one of the possible futures of music, don't miss his final Sydney lecture - demonstration in the Science Theatre tomorrow night. Whether you like the sounds he produces or not, you will be fascinated by the exposition and by the horizons it opens up.

Stockhausen's third recital [16]

By ROGER COVELL

Stockhausen's third lecture - demonstration in the Science Theatre at the University of N.S.W. last night was both less and more illuminating than his two previous appearances there. Less in the sense that the philosophy and poetry of his music-making were not as relevant to his topic on this occasion; more in the sense that he took us - or perhaps gave the illusion of taking us - a little more searchingly into the architecture of his sounds. With the aid of two boards and coloured chalks he represented graphically some of the principles of sequence and structure in one of his well-known electronic works, "Kontakte." In the process he proved his own contention that Western man has largely lost his belief in any kind of truth other than visual truth. Aural truth which does not square with our visual impressions is discounted; and for many people aural logic only becomes evident if it is first translated into visual terms. In talking about the principle of composition and decomposition of sounds in electronic music, Stockhausen undoubtedly made his point more easily because of the shapes he had already drawn on one of the boards. Sounds detached themselves from a thick, apparently single line (equals sound) in ascending or descending spaghetti shapes, disclosing at the same time that the original sound was not homogeneous but had several components. "Decomposition", in other words, was a revelation of the elements that had formerly been disguised as an entity. Hardly less fascinating was Stockhausen's concept of "multi-layered spatial composition” especially when he translated this abstract mouthful into the metaphor of opened and closed curtains of sound. When a curtain is opened it discloses new vistas, new curtains behind it. Sound which is soft may appear close; loud sound can be appear distant.

The emancipation of musical accents which began, according to Stockhausen, with the 18th century Mannheim school and C.P.E. Bach, has now begun to accelerate with the combinations of emphasis and distancing that can be achieved with the fitting together of up to five vistas of sound. Stockhausen probably clarified many of his listeners thoughts on the antithesis of music and noise when he reminded them that it was a cultural habit of Europe to think of music as heavenly, and noise as actively diabolical.

These newspaper reports reveal the polymath in Stockhausen – composer, performer, scientist, philosopher and teacher. His radical, activist stance, and Dadaist approach which sought to directly confront the public with his art, was seen not only as that, but also innovative and refreshing. As a result, the anonymous Sydney Morning Herald writer of March 1970 was correct in his prediction that the visit would have reverberations long after his departure. Evidence of this was not long in coming.

Hobart

On 7 December 2007 the following reminiscence was posted by stefank at the SaxontheWeb.net site at the time of Stockhausen's death:

I remember a concert he gave here in Hobart in either 1969 or 1970. Being an unsuspecting teenager I really had no idea of was was going on at all, save that (with the audience seated in the midst of four speakers, and Stockhausen controlling things from the middle) it was the loudest musical event I had ever attended. It took quite a few more years before I could start to make sense of works such as Kontakte and Hymnen. I'm glad I was there though, to witness one of the most significant members of the avant-garde in the music of the second half of the twentieth century.

---------------------

At the Yellow House

In June of 1970 performances of Stockhausen’s composition Hymnen were held at Martin Sharp’s multimedia performance and exhibition space in Sydney known as the Yellow House.

|

| Repeat Performance of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s “Hymnen” [advertisement], Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 1970. |

The facility – a three storey Victorian era terrace building - had opened in May 1970 within the old Clune Galleries at 57-59 Macleay Street, Potts Point. Initially an exhibition was held there comprising works Sharp had completed in England during an extended stay from June 1966 through to the end of 1969. The building had recently been abandoned prior to redevelopment and Sharp was given free reign to take over its many spaces in the interim. With the success of his initial show, he then opened the facility to other artists and created the Yellow House, inspired by Vincent van Gogh’s attempt at setting up an artists’ community in Arles during the 1880s. Artists and performers gravitated to the Potts Point terrace and ideas and opportunities quickly grew. The Yellow House was a hive of activity during 1970-2, providing both venue and shelter for literally hundreds of local artists, like-minded supporters and visitors from near and far.

Hymnen was noted as an ‘electronic and concrete work, with optional live performers, composed in 1966-67 and elaborated in 1969.’[17] Precise details of the Sydney performances at the Yellow House and the players involved are not known at this stage, though there are reports that local dancer and avant garde artist Phillippa Cullen (1950-75) was involved.[18] Both Stockhausen and Cullen made use of electronic instruments and sounds within their performances. Whilst Stockhausen was in Australia, Cullen travelled with him to Hobart, assisting with equipment setup and performance.[19] She later travelled to Europe in 1973 on an Arts Council scholarship and took the opportunity to work with Stockhausen in his studio. At one point Cullen staged a performance there, dancing with a Theremin connected to a synthesiser. Also during that year Stockhausen began work on the orchestral composition Inori. According to one account, ‘It was Phillippa Cullen’s gifts as a dancer that gave Stockhausen the idea of having dancer-mime portraying prayer gestures along with orchestral music.’[20] Unfortunately Cullen's untimely death in India during 1975 brought an end to any possible future collaboration. Both artists worked in a similar area of performance wherein new technologies were utilised to enhance the experimental nature of their work. Cullen sought to link dance with music, such that the dancer became the composer. She utilised electronic devices such as the Theremin, television screens, sensitized floors and synthesisers to do this. As Stockhausen worked in the area of electronic music composition there was a natural affinity between the two, at least in the area of their work, if not personality wise.

Following the Hymnen performances in June, throughout July 1970 concerts were held at the Yellow House by local singer Jeannie Lewis, who has starred in Love 200. This was followed by a performance from composers Ian Farr and Richard Meale. The Yellow House then closed as a public performance space for a period, reopening in March of the following year. During the intervening period the building was transformed inside and out from a traditional art gallery into a work of art by Sharp and his friends, with many of the rooms painted according to various art historical and contemporary themes. Spaces for performance were also put in place.

By staging Hymnen at the Yellow House, the work of Karlheinz Stockhausen was brought before an audience of local artists and performers keen to integrate his ideas and music into their own work. As an enclave of the avant garde and bohemian free thinking in Sydney, the Yellow House provided a perfect, if small, venue for an audience keen to be exposed to the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1970. The fact that the following year the English rock band Pink Floyd would hold their Sydney press conference in the Yellow House is testament to the synergies between innovative and experimental art, music and performance then at play.

Herald journalist Romola Costantino noted, somewhat venomously, that during July 1970 David Ahern was ‘busy organising concerts to promote extreme works form the schools of Stockhausen and Cage, and others of similar convictions.’[21] Costantino was not a fan. On 21 and 22 September 1970 two ‘Prom’ concerts were held in the Cell Block Theatre, National School of Arts, Darlinghurst, Sydney, with a number of performances including Stockhausen’s ‘Piano Piece IX’, ‘Adieu’ and ‘Solo’. Reviews by Roger Covell noted the ‘characteristic devotion and flair’ by Ian Farr in regards to the first piece, along with the inspirational use of flute by Peter Richardson in ‘Solo’, intermixed with tape-recorded playback. The loudness of the latter forced the reviewer to seek refuge in the back of the hall.[22]

Stockhausen’s music and performance continued to influence Australian musicians through the 1970s and beyond, with the avant garde mixing with pop and classical as the local music scene evolved. His brief Australian tour of April 1970 played a small, though significant part in the internationalisation of Australian musicians and composers.

In January 2020 the 50th anniversary of Stockhausen's visit to Launceston was celebrated at the Albert Hall with performances of Telemusik and Upwards - both of which had been performed in the hall back in 1970.

----------------------

References

[1] Excerpt from an undated newspaper clipping, Melbourne, April 1970. Source: Percy Grainger Museum Collection, University of Melbourne.

[2] Buckminster Fuller, Wikipedia, 2019.

[3] Expo (Stockhausen), Wikipedia.

[4] James Humberstone, The Music of David Ahern, Master of Music thesis, University of Sydney, March 2003, 152p. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4330.8568.

[5] Brief visit to rock world of music, Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 11 March 1970.

[6] F.R. Blanks, Earth Shattering End, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February 1970.

[7] Independent Selection – Coming Events, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 February 1970.

[8] Karlheinz Stockhausen Visits Australia, Australian Journal of Music Education, 6, April 1970.

[9] Protest drowned his first composition; now he’s Master of ‘machine made music’, Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 11 April 1970.

[10] Newspaper clippings of Karlheinz Stockhausen in Australia, 1970, Grainger Museum, University of Melbourne.

[11] Karlheinz Stockhausen, visit to Australia 1970, Rudolf Pekarek Collection, Folder 2, Box 3, UQFL153, Fryer Library, University of Queensland.

[12] Jarrod Zlatic, David Ahern & Vexations & The Avant Garde in Sydney, 1970, JZ [blog], 3 January 2014.

[13] History of the Electronic Music Unit, University of Adelaide. Available URL: https://music.adelaide.edu.au/emu/history/.

[14] Roger Covell, Stockhausen mixes humour, feeling, Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 1970.

[15] Roger Covell, Poetic consistency and logic in Stockhausen, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 April 1970.

[16] Roger Covell, Stockhausen’s third recital, Sydney Morning Herald, Thursday, 16 April 1970.

[17] Hymnen, Wikipedia, 2019.

[18] Stephen Jones, Phillippa Cullen: Dancing the Music, Leonardo Music Journal, 14, 2004, 64-73; Keith Gallasch, Tribute to a pioneering dance media artist – Stephen Jones, Dancing the music: Phillippa Cullen 1950-75, Realtime, 134, August-September 2016. Available URL: https://www.realtime.org.au/tribute-to-a-pioneering-dance-media-artist/.

[19] Michael Kurst, Stockhausen: A Biography, Faber & Faber, London, 1992.

[20] Op. cit., 196.

[21] Romola Costantino, What Kind of Noise …? Sydney Morning Herald, 6 July 1970.

[22] Roger Covell, Jazz Put Audience at Ease, Sydney Morning Herald, Tuesday, 22 September 1970; Music Cocktail, Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday, 23 September 1970.

--------------------

Last updated: 12 March 2021

Michael Organ, Australia

Comments

Post a Comment